Creating the Gacha & Catch Pop Up Shop: An Interview with a Mitsubishi Spokesperson

Interior of the Gacha & Catch pop-up store.

Interview by Brooklyn

Gacha culture is a mainstream form of entertainment in Japan involving small prizes of various kinds inside little capsules as well as mechanical crane games. On 22 November 2025 a pop-up store featuring these gacha machines and crane games will be opening in 1451 3rd Street Promenade, Santa Monica, CA 90401; a project that is a year in the making.

Your backdoor anime hangout had the opportunity to not only tour the location, we had the utmost pleasure in interviewing the Senior Manager of IP Value Chain Business Team, Smart-Life Creation Group, Mitsubishi Corporation.

Brooklyn (B): Why did you choose Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica?

Senior Manager (S): Santa Monica is a symbolic location that represents California and Los Angeles. It's also highly recognized so I selected this location.

B: Since gacha culture is different in Japan than here as we see it in the U.S. more in a mobile format and in Japan it's more analogue, what was your goal in bringing the physical gacha experience to Los Angeles?

S: We have prepared a variety of unique Japanese experiences and products. Additionally, we are offering items that are difficult to obtain in the U.S. market, I think. Allowing visitors to experience Japanese culture, cutting-edge entertainment firsthand. For example, with gacha, we want visitors to enjoy the exciting thrill of not knowing what they will get. So gacha is the point. And the crane game, we hope they experience the fun of catching and winning the prize. So I think that the shops combine these elements. It's something you rarely see in the United States so I expect the success of this shop.

B: I know there are different animes and things that are featured in the machines here. Was there a process in which ones were selected?

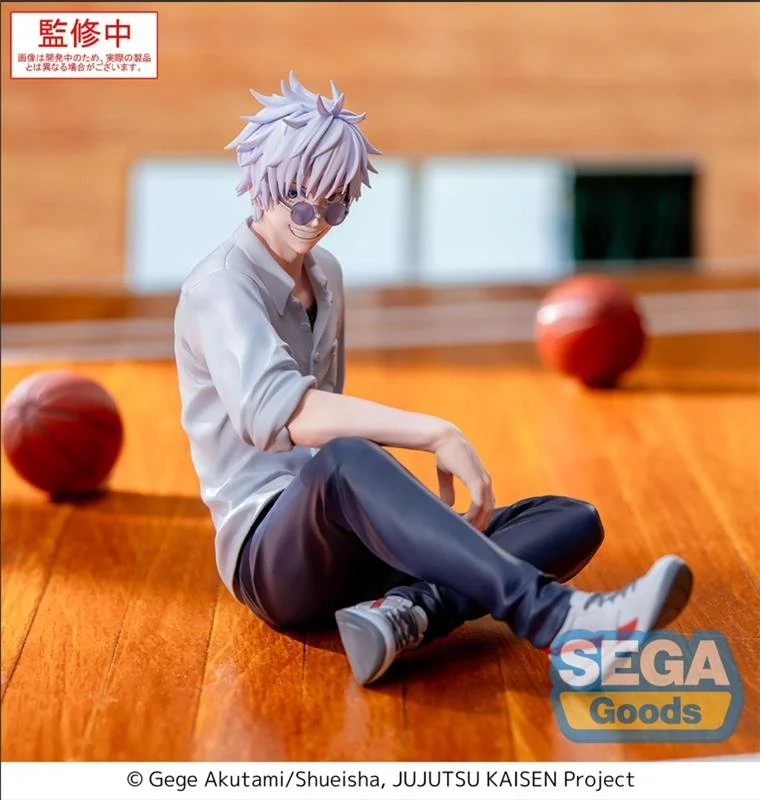

S: SEGA and TOMY have good relationships with all IP characters, IP products and IP companies like Sanrio or Disney. And also they choose some collected data of which characters are famous or not famous.

B: Oh, in the U.S. specifically?

S: Not U.S. specifically. It is based on the Japanese record; the Japan market. But thanks to Netflix and Amazon Prime, Japanese anime recognition is going up in the U.S. market. So we know which anime or which character is famous or not. So we utilize that kind of data.

B: What do you think people don't see in the preparation for this event; for the release of this pop-up that you want them to recognize?

S: So our products, the kind of shop concept is Japanese “kawaii.” So therefore we face the challenges of finding locations. Because that would appeal particularly to young generations and families; which area is suitable for that kind of targeted customers. Additionally, preparing to ship new and famous Japanese products to the U.S. market. And also adjusting the crane machine for U.S. instructions, U.S. specifications. So that's a significant challenge.

B: So what do you mean by U.S. specifications for the machines? Is it the way they're set up like calibrations and PSI on the actual cranes themselves?

S: Yes. And also the price. We have to pass a test for U.S. market because of the toys. Everything has to adjust for U.S. specifications.

B: Are you going to expect any other pop-up or “Gacha & Catch” launches in the future?

S: Yeah, we focus on the success of these shops first, the Santa Monica shops. And if it is accepted well - well-received by U.S. customers here - after that, we plan to expand this kind of store operation further more. And we aim to roll out these kind of shops more not only in Los Angeles, but also across the U.S. like Texas.

Exterior of the Gacha & Catch pop-up shop

B: Are there any plans of turning this pop-up in particular into a permanent shop?

S: First of all, we focus on the success of the store. If okay, well received by U.S. customers, we extend permanently the shops. And also we try to expand the other locations.

B: Was it part of your strategy to release this pop-up during the holiday season when there's going to be more people celebrating for the holidays?

S: Yeah, I think so. Thanksgiving, Black Friday. We have to achieve that open date. November 22nd is important for us because before Thanksgiving, before Black Friday, and also the Christmas season, so this conceptually is very high.

B: Thank you very much for giving us more insight into what's going on here. We really appreciate it!

S: I'm also appreciative for your interview, I'm very excited to open the store!

Store launches on 22 November 2025 on 1451 3rd Street Promenade, Santa Monica, CA 90401.

For more details please visit the Gacha & Catch website.

Many thanks to:

Brooklyn for conducting the interview.

The Senior Manager of IP Value Chain Business Team, Smart-Life Creation Group, Mitsubishi Corporation for their time and expertise.

Maddie Morrow of Thirty Three USA for the press invitation.

Boldly Go Ghost Cat Anzu!

A tale of two studios by two directors about two oddballs.

A Tale of Two Studios, Two Directors, & Two Oddballs.

by Jonathan Beltran

Karin, the reluctant city girl, and Anzu, the middle-aged ghost cat.

Vision is the bedrock for any creative project, with animation the sky is truly the limit.

Before an explanation of the plot, Ghost Cat Anzu has a fascinating production background. Producer Keiichi Kondo pitched an adaptation for Takashi Imashiro’s manga of the same name, notably utilizing different production techniques including live action and rotoscoping - an animation technique wherein an animator traces over real live footage frame-by-frame to depict movement. Enter directors Nobuhiro Yamashita and Yôko Kuno.

From left: Directors Yôko Kuno and Nobuhiro Yamashita

The former is an acclaimed live action director with a line of films depicting loner life and drifter characters from his debut feature Hazy Life (1999) to Over the Fence (2016). With regards to his first film, Yamashita has a keen eye for disenchanted characters trying to get by through the inconveniences of the modern world while finding joy in the most minute of places; whether that be a cigarette exchange or the imagined fantasies of what could have been.

The latter is a well-respected animator in the scene. From her graduation film Airy Me - an animated music video featuring Japanese musician Cuushe - to her rotoscoping work on anime such as The Case of Hana and Alice, Kuno has a knack for meticulously detailing motion through wild and poignant experimentation. Look no further than her brief animation, Roto Spread, wherein her rotoscoping talents are on full display - transforming two babies playfully interacting with one another into various different animals and shapes. If there is motion there is a story.

The long and short of this duo’s directorial role, Nobuhiro Yamshita shot a live action version of the film serving as the firm foundation for Yôko Kuno and company to carefully animate each little movement and expression.

Another notable feature is its international collaboration with two studios: Miyu of France and Shin Ei Animation of Japan. Miyu has previously worked with Japanese filmmakers since 2017, yet this film marks a rare chance to work with a major Japanese studio known for titles such as Doraemon, Crayon Shin-chan, and Teasing Master Takagi-san. Given the Japanese anime market leans heavily on a domestic audience, funding a project such as this was going to be a challenge. According to an interview with Yôko Kuno, Miyu approached her first for a potential project and Ghost Cat Anzu became that. Ergo Miyu’s creative and financial input brought not only the necessary funding and artistic vision to light, but also opened a way for potential interest in the world wide market. Thus, at least within the North American market, GKids picked this title up for further distribution - screening in noteworthy Western film festivals such as Annecy, Cannes, and - most recently - Animation is Film.

From left: Director Yôko Kuno and Producer Keiichi Kondo at the Animation is Film Festival 2024.

With all that said, how does one adapt a manga about the episodic adventures of a middle-aged anthropomorphic cat helping out his fellow villagers into an animated feature?

Simply add an eleven year-old brat to the mix.

The brat in question, Karin. Do not be fooled, or else become the fool.

Ghost Cat Anzu is set in a rural town and follows a disgruntled young girl named Karin (voiced by Noa Goto) who is left at her grandfather’s home after her father leaves to pay off his debts to loan sharks. During her stay she meets Anzu-chan (voiced by Mirai Moriyama) a thirty seven year-old ghost cat who regularly helps the elderly in the village. Anzu is given the responsibility of looking after Karin, while Karin finds ways to run away from it all.

The centerpiece of the film lies in the personalities and relationship between these two characters, namely surrogate parent and child.

An original character made specifically for this film by scriptwriter Shinji Imaoka, Karin has terrible circumstances: the aforementioned deadbeat dad who cannot seem to pay off his debts back home in Tokyo and a recently deceased mother all culminate in the reluctant retreat to the countryside. She may be going through hell, yet she is by no means innocent. Atypical from many young girls in anime marked by their innocence and purity, Karin is discontent and manipulative - taking cues from her father to ask money and favors in the guise of pity whether it be from boys or local yokai; using her age and backstory as leverage to get what she wants. And yet the film makes it clear that Karin is a hurt and lonely girl. There is a poignant scene where she sees a family playing on the beach - mother, father, and child all having fun - and in disgust pushes their bikes into the ground; a reminder of a dynamic she has lost and can never get back. Karin is less cold-hearted, and more desperate for some semblance of control in her otherwise chaotic life.

Anzu-chan is in many respects what you would expect if one were to fully realize “being a cat” as a personality: prone to anger, impolite in his behavior at home (ala urinating in the front yard, a shrine no less), and at times lazy - Anzu is not necessarily parent material. Yet between him and the aforementioned father, there is not much competition for Karin - or more fittingly not much of a choice. However outside of his slacker demeanor, he has a compassionate heart for his neighbors. One instance involved getting rid of the poverty god’s presence in his friend’s life just so that he can graduate from having bad luck to now having average luck. He is more or less a happy-go-lucky cat that takes on life as it goes, serving as a greater foil to Karin.

Karin and Anzu at Tokyo Station.

Both are at odds with each other. It is a given that Karin will not yield to parental figures, yet is especially true towards Anzu. After Anzu calls Karin a liar for manipulating forest spirits in giving her money and pity, Karin orders one of the children to throw Anzu’s bike into the river. Yet this also demonstrates the dual compatibility between the two. Both Anzu and Karin have both lost their mothers over time and are raised by their respective fathers, yet while Anzu has grown up and seemingly passed the grieving stage - a brief depiction told in photos - Karin is stuck; looking at her screen saver of her family when they were at their happiest. Furthermore, Anzu is willing to accompany her all the way from the boonies to her home in Tokyo for the sake of her safety, while Karin reluctantly invites him into her messy life - a front door filled with thinly-veiled threats from loan sharks directed to her father and her mother’s gravesite, which unfortunately could not be accessed due to unpaid bills. This is particularly emphasized where the poverty god makes a repeated appearance to give Karin bad fortune. Anzu makes a wager for him to leave only for the poverty god to refuse it, all while Karin - who cannot see the poverty god - is left looking at Anzu making an invisible deal. Their adventures and misfortunes pull them further together, sharing in the misery while finding avenues for safety and security - for Anzu’s its Karin’s wellbeing, and for Karin keeping all that she has from what has already been lost.

This all culminates to a suspenseful and action-packed third act involving the beauty of Tokyo and terror of Hell. While not much can be divulged without the risk of spoilers, it is worth mentioning the lengths with which Karin is willing to go to get what she wants. And to its bittersweet end comes the sobering realization that there is only so much one can do to change their circumstances, yet there is so much one can do to change their perspective. Given that Karin is the main character in all of this is fitting and appropriate.

All that said, considering the production and animation process how much does this all pan out? Ghost Cat Anzu’s lively and fluid animation depicts the nuances of human motion and a playfulness in its expression - a testament to Kuno’s vision and Yamshita’s live action direction. There is a beautiful scene where Anzu is eating a crepe and the people around him walk, order crepes, and take photos - it is simple yet displays how much of an observer’s eye the animation department put into the film. This production choice emphasizes the forward and living movement of time, a concept fitting for a child learning what it means to appreciate life for what it is and hope for what it could be. However, the audio is noticeably off. It does not happen often however there are lines that either do not complement the animated expressions - an exaggerated angry character design does not match the energy of a more subdued portrayal from its live action foundation - or has a distinguishable echo/muffle in the recording. While minor amidst the rest of the film, it can take out the viewer’s immersion.

With regards to the creative collaboration there are beautiful backgrounds crafted by Julien de Man of Miyu wholly “reminiscent of Pierre Bonnard’s neo-impressionist works.” It is a vibrant and colorful dirge that brings out the life of the village; brilliant hues of yellow, pink and green decorate the landscape. Beauty and light surrounds the characters on earth, which makes the trip to hell all the more stark in its cold and somewhat corporate look. One can certainly tell the mutual respect each studio had for one another as well as the bold directions they were willing to go to tell this story.

Background art done by Miyu’s Julien de Man.

With all that is said and done, will this hopefully set a new standard in Japanese production? Depending on the success of this film, it may potentially happen. Perhaps not within the local domestic Japanese anime market, however for more independent cinema there is hope. As mentioned previously, Miyu approached Kuno first thereby implying an informed and engaged worldwide animated industry willing to work with talented Japanese artists.

Ghost Cat Anzu is an admirable work of collaborative art. Two studios from two countries, by two directors from two different backgrounds in filmmaking all coming together to craft one movie of two charmingly unconventional characters becoming one odd family unit. It is a story that has been told a thousand times, yet nothing quite like this. It may take a village to raise a child, yet it takes one person - maybe even a middle-aged cat - to make a difference.

If you know, you know.

Ghost Cat Anzu will be in theaters on 15 November 2024.

Many thanks to 42 West LLC for the screening and interview opportunity.

The First Slam Dunk: Style in Sweat and CG

Style in Sweat and CG

by Jonathan Beltran

There are shows and movies considered to be legendary; influential to the medium and a generational marker for the masses. Slam Dunk is no exception. Originally a manga and later adapted into an anime in the nineties, Takehiro Inoue set out to create a compelling story capturing “the feeling one gets from playing sports.” That feeling, to my understanding, is adrenaline.

Slam Dunk stars Hanamichi Sakuragi, a delinquent who consistently gets rejected by his crushes, usually because they love someone from the basketball team. Ironically he joins one in order to impress his crush, Haruko Akagi, and learns the tools and techniques of the trade as he competes. Most of the time he fails, and gets fouled out often, though much like every good shounen protagonist, you come to love the underdog; the growth, progression, and maturity for your main character. He learns to shoot and even, no surprise, slam dunk! Together with captain Takenori Akagi, Hisashi Mitsui, Kaede Rukawa, and Ryota Miyagi they form the Shohoku basketball team in the hopes of becoming champions in the Nationals. All of this, I came to learn AFTER watching the latest film and sequel The First Slam Dunk.

I knew nothing of the series going into The First Slam Dunk. A good number of friends and colleagues have told me of its quality, even so far as to claim its renown across Asia, specifically China, South Korea, and Taiwan. And when I came to its US Premiere at Anime Expo 2023 there were plenty of Slam Dunk fans - some even cosplaying in red Shohoku jerseys and basketball shoes. And to top it all off, this was going to be directed by the mangaka himself; his directorial debut. There was no doubt in my mind that this has been long awaited (twenty six years in fact).

The First Slam Dunk stars Ryota Miyagi, Shohoku High School’s premier basketball point guard, in his origin story as well as the followup basketball match between Shohoku and their rivals, Sannoh. It is important to note the pattern of this film. It begins with Ryota’s past and is followed by the aforementioned game then goes back-and-forth from there; informing each other to show the depth of his (and by extension his teammates’) passion for basketball. In other words, if you are coming to this fresh - like I did, you can rest assured that you and everyone else will be thrown in the deep with enough context to sustain you.

The film gives a bird’s eye view into Ryota’s tragic backstory - first the loss of his father and, later, the loss of his brother; the latter being the inspiration for his love of basketball - with such intimate depth that it can get too real. There is a scene involving a young Ryota fighting his mother to keep whatever was left of his brother - a jersey, trophy, stack of basketball magazines - with him protecting the box as his mother tries to pull him away from it.. Inoue’s approach reveals a level of visceral traumatic humanity in this scene not found in the original anime that paints the drama for Ryota not only in the family, but also in the court.

On the court is a sweat-inducing dirge for everyone involved - athlete, coach, and spectator. People are passing the ball to one another, shooting free-throws, stealing and saving balls; all the typical sports anime forray. What The First Slam Dunk does uniquely is provide a sense of dramatic and comic urgency with every action. Each fake-out is equally witty as it is vital, facial expressions point out who’s ready to receive the ball are personal and endearing, and even the group huddle is hilarious with team captain Akagi stating that everyone of his teammates has pissed him off for the most part. These scenes reinforce the down-to-earth tone that makes this movie, and the franchise, so distinct from its contemporaries. Ryota Miyagi relies on his teammates just as much as he does with his family - broken in their own unique way yet come back together for one shared cause.

When comparing the series and the movie, I am surprised at just how cinematic and accessible The First Slam Dunk feels. Not to say the anime series is not that, though the tone is relatively different. There is a somberness to it that can feel sobering for anyone who has watched anime for the longest time. Gone are the silly chibi’s for gags or the goofy antics, this is primarily humbling. It may have certain tropes - believe hard enough you can get past the pain for instance - though it maintains a sort of maturity different from Slam Dunk. Inoue notes of the shift as well in the storytelling process stating “[T]wenty-six years have passed since then [the publication of Slam Dunk] and my perspective and value have shifted[/increased] a lot. I learned that there is a lot of pain and a lot of things that just won’t work…Sometimes we hold that pain and sometimes we can overcome the pain. I wanted to depict the film from that new perspective.”

Now to address the elephant in the room, The First Slam Dunk opts for 3DCG animation. There are those who are wary of its choice, though I can say for the most part that it serves the movie well. This is a collaborative effort between Toei Animation and Dandelion Studios, the latter has worked on titles such as Lupin III The First, Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero, and scenes in another popular sports series, Haikyuu!!. In my experience it does take a while to get used to, however it will not take long. As soon as the basketball match happens the 3DCG animation really flexes. This choice allows for the viewer to feel the rush of adrenaline as players run towards the basket as if they were in the court. There are 2D scenes as well, specifically in more still, quiet moments such as conversations between characters. However there is a scene near the end - the final few seconds of the game - where the animation turns into a stenciled fever rush. When I was watching it at the Anime Expo, everyone in the audience was at the edge of their seats. Inoue and team knew where to flesh out tension and this scene alone is a monumental moment.

The First Slam Dunk is nothing short of amazing. It is a reminder of how legendary both the Slam Dunk franchise is as well as Takehiro Inoue is as a storyteller. Palpable drama can be felt from every action on and off the court while maintaining the thrill of a potential victory. In a time where anime reboots are populating the market refueling nostalgia, this film is a testament to proving its greatness.

Many thanks to Brett Myers and Anisha Chen of GKids for the invitation to watch The First Slam Dunk at Anime Expo and Scott Barretto of AMC Networks for ushering me to the press seating.

The House of the Lost On the Cape

Pressing on past trauma through community and the supernatural.

Healing Past the Trauma

In the days of yore, a saying came to my mind “Wherever you go, there you are (credit goes to a mentor of mine back in college).” As a youngling I didn't quite get it. Years pass and the meaning becomes clearer - no matter where and how far you go, you still bring your hopes and fears, wants and needs, and - in this case - presence and trauma.

The House of the Lost on the Cape is a 2021 david production (Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure, Cells at Work) animated film based on Sachiko Kashiwaba’s novel, Misaki no Mayoiga. Production credits include Shinya Kawatsura (Non Non Biyori, Kokoro Connect) as director, Reiko Yoshida (Liz and the Bluebird, K-ON!) as a screenwriter, Kamogawa as character designer, and Yuri Miyauchi as a composer. This lineup, especially considering the director and screenwriter’s resume, means that this movie may make you cry.

In the aftermath of a destructive earthquake, Kiwa Yamana adopts two girls - Yui, a teenage runaway, and Hiyori, a mute orphan - as her granddaughters and takes residency at a cliffside house. As days go by, Yui and Hiyori come to encounter supernatural occurrences one being the house they live in called the “mayoiga,” a mystical and hospitable entity of Japanese folklore that provides food, shelter, and all other homely necessities to the community. Eventually, more mythical creatures come to visit the house thus prompting the question: who is this lady, and why are they adopted in the first place?

An important note is that The House of the Lost on the Cape is part of a promotional initiative called the Continuing Support Project 2011 + 10 (Zutto Ouen Project 2011 +10) commemorating the 10th anniversary of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami; the Iwate prefecture, where the movie takes place, is heavily impacted. Opening the film is a walk through the rubble; buildings reduced down to their barest elements on the ground, a bridge still standing with rusted and bent railings, and out in the distance a calm sea; an ironic sight considering the tsunami. People of the town are getting by with relief and aid, yet are wracked with an impressionable loss in various shapes and forms, normally loss of immediate family members.

Steady and heavy is the best way to describe the atmosphere. In addition to the community’s loss, Hiyori and Yui have their own trauma. Hiyori anxiously runs out of the room hearing the traditional fox dance song, to avoid thinking about her parents’ funeral. Yui also does this when she sees her abusive father shopping at the local store she works at. No matter the distance they have trekked from, both still are haunted by painful memories. Screenwriter Reiko Yoshida, masterfully imbues emotional potency that captures traumatic apprehension with few words and haunting humanity. Where it becomes moving is when the trio are together sharing the joy, sorrow, hope, and fear of the past with a loving presence. A scene that emphasizes this is when Yui opens up to them about her experience with an abusive father. A lot of shame, guilt and anguish is expressed in this moment and is met with Kiwa gently reassuring her strength as a “sincere and tenacious” spirit, followed by Hiyori silently leaning onto Yui’s back. Then Yui cries. What a simple and powerful act of compassion and community; one that Yui and Hiyori so desperately need. This scene proves that director Shinya Kawatsura and screenwriter Reiko Yoshida are masters of capturing intimate moments.

Kiwa Yamana is an enigma. She is both a loving and empathetic grandmother who graciously helps those in need, especially to her granddaughters, and one of the few in the world to actively interact with the supernatural. Her presence serves as the connective tissue to the film’s heart and soul - building a sense of belonging amongst those she encounters while protecting the hope inside everyone with the gentlest touch and sensitive voice.

This film makes mystery and community prevalent and inseparable. There is a sense of fellowship and synergy in the local and mystical. Mankind continues to pick up the pieces and live normal lives - jobs, school, community gatherings. Then there are the “enigmas” - mystical spirits of Japanese folklore that - in this movie - support humanity. These beings are invisible to the world at large and are omniscient to the plights of humanity. And it is through the care and respect of the human community - both by the trio and the town - that life can be sustained. Look no further than the mayoiga itself, centuries of providing food and shelter for the community. And the mayoiga continues to improve when people take care of it - cutting the grass, cleaning the floors, and hosting dinners. This further enhances the movie’s push for the community as an essential piece for resilience in tragedy.

Composer Yuri Miyauchi laid a fine and memorable soundtrack that not only complements the aforementioned steady and heavy atmosphere, but it also accentuates. There is a tenderness to his composition that breathes levity and yearns for innocence for the hurt Yui, Hiyori, and the rest of the town have to endure. It sounds like a heart processing pain while simultaneously playing around. For those who enjoy the subdued tones of Kensuke Ushio’s A Silent Voice and Yoshiaki Dewa’s soothing acoustic musings on Flying Witch, Miyauchi’s contributions are within that vein.

Now as mentioned extensively, this is a slice-of-life picture with an emphasis on healing, so it may potentially be slow for others. It is a movie that is unashamed to address suffering and has sparse moments to take it all in, for some it may be needed, and for others, it can be a drag tone-wise. Along with that comes the jarring climax. Thematically it is sound, the execution, though, is lackluster. Without giving too much, it becomes an action movie for a few minutes the buildup felt rushed ergo the payoff suffers. A part of me wanted more time, development, and genuine struggle from these characters - ironically these people have suffered enough, though some more scenes of the village, the enigmas, and even Hiyori and Yui reacting to the situation would have made the climax more engaging.

A well-intentioned project such as this provides an approachable awareness for the viewer - the scale of the destruction, the mental toll people have to carry, and the hope for humanity to thrive. Disaster may lay waste, yet succumbing to our fear leads to the “real ruin.” When everyone leaves believing the lies of potential futility that is the true disaster. As the saying goes “wherever you go there you are,” and yet the film provides an optimistic extension. The House of the Lost on the Cape demonstrates the importance of a committed and compassionate community in its capacity to hold the collective trauma everyone uniquely undergoes and resilience to overcome such catastrophe. Although one cannot erase the pain from the past, the present love and hospitality can provide a hopeful future. For that, I believe it succeeds.

Many thanks to Deborah Gilels of LA Media Consultants and Eleven Arts for the screener opportunity.

The Deer King Review

Of family and kingdoms, which do you pledge your allegiance to when the world tears itself apart?

Of Kingdoms & Family, Pledge Your Allegiance

The Deer King is a 2021 debut film for directors Masashi Ando and Masayuki Miyaji; the former helms storyboarding, chief animation, and character design for this movie working previously as animation director for Spirited Away, Paprika, and your name. to name a few; the latter also does storyboards for the movie and worked as an assistant director for Spirited Away as well as a series director for Xam’d Lost Memories and Fusé: Memoirs of a Huntress. A promising duo nonetheless.

Set in a medieval fantasy, the Zol kingdom reigns over its rival Aquafa, yet the Zol are the primary victim of the mysterious Black Wolf Fever, killing every class of Zol citizenry/lineage from prisoners to high court officials. Caught in the fray is former Aquafese military leader, Van, as well as his newly adopted daughter, Yuna, an Zol orphan in the mines. Together they venture onward, fighting to stay together in a world that continues to tear itself apart politically, medically, and relationally.

This feature is as straight-forward as it goes, and I personally like that. Anchoring this is an emotionally driven narrative of Van and Yuna forming a familial bond. It is genuinely heart-warming to see these two interact from Yuna sharing a piece of bread to Van to Van pursuing the wolves to rescue Yuna’s life. A lot of this can be attributed to the duo’s loss: Van lost his family in the midst of the Black Wolf Fever and Yuna’s only guardian mauled by a Black Wolf. Both characters depend on one another in their own unique way, Van as the obvious parental figure in Yuna’s life, and Yuna’s cheerful demeanor and affection rekindling Van’s fatherly love. It is nothing short of effective and relatable. Yet this is where the “to-the-point” story can be a double-edged sword. Take it as is, and you can enjoy the ride just like I did. However, those who want more than what is presented, you will not find this engaging.

From left to right: Yuna and Van

This trickles down to the characters as they are simple, motivated, and functional to the plot. There is not a lot of depth with any of these individuals as they are servicing the story and nothing more. Van wants to protect Yuna as a father who lost his own kin, Yuna wants to be with Van as he is her only guardian, and the medical examiner and doctor, Hohsalle, wants to find the cure for the disease plaguing the world. These are archetypes that simply service the grander narrative as opposed to characters one can sink their teeth in. For some it can be a disconnect, and for others, like myself, is not a problem. I cannot really pinpoint a reason other than it works effectively.

Complementing the main plot of familial bonds is the fight for humanity. There is a particular scene wherein Doctor Hohsalle argues for a cure to a military general hellbent on overthrowing the Zol Kingdom claiming it is humanity’s pursuit to defy destiny; the latter being the general’s reasoning for the Zol’s lack of immunity. A provocative claim considering the body count of lost lives due to the illness, furthering the film’s point of bridging connection.

Hohsalle

This film echoes that of Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke as it involves a plight of humanity, the might of nature, and a noble warrior fighting through his way in all the sensory chaos. It is no surprise as Masashi Ando had worked on the project as a character designer and an animation supervisor. As impressive as this feature may be, I am left wanting more from The Deer King - presentation, plot, and ending (the latter will not be spoiled).

This is a very exposition heavy film. Turn your head away from the screen or some other minute form of distraction you will lose a key detail in the world-building. There are a lot of involved moving parts that make the world as it is and to miss it will leave your head scratching. In my view it is a well-oiled machine, you just need to pay attention.

Plot details are fine, though some parts lack significance, weight, and stakes. The coming of the emperor is made out to be a titanic event for the kingdom, immense balloons are hoisted from the ground to guide his airship towards the de facto location as well as this becoming a ripe opportunity for assassination. What is not mentioned is how important he is to the world as opposed to an element to drive the plot. What is he to his subjects, nearby villages, and the kingdom as a whole? And if he is lost, what will be the cost? One can only infer.

The ending is what continues to boggle my head the more I think about it. Without giving too many details, the film communicates very clearly that it is a noble feat. One can say it is purposeful and another can argue it is under-developed. Passing days have made me side with the latter simply because of my dissatisfaction. Though at this moment and time, I think once again of the details I may have missed and overlooked and now lean towards the former. In other words, the movie “clicked” for me.

This movie leaves a lot to be desired. On one end, I want more world immersion through a more expansive world, or perhaps a more focussed one solely on Van and Yuna. Then again, I miss straightforward action-adventure films where characters can simply function in service of the story, and with the emotional potency of a familial love - especially one between a Aquafese widow and a Zol orphan - it is truly a refreshing one to boot. And as mentioned previously, it continues to grow the more I think about the details, plot, themes, and previously held problems of the movie.

The Deer King is a promising debut for both Ando-san and Miyaji-san who have shown their competency as storytellers. Both have learned from the greats and worked with the greats, enough for me to look forward to their upcoming projects and overall progression. May they continue on their creative paths towards greater, focused, and inspired projects.

The Deer King is distributed and acquisitioned by GKids and is currently in theaters at the time of this review. Tickets here.

Many thanks to Sophia Kandah of 42WestLLC and GKids for the screener.

Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko: Review

Small town charm with a warm welcoming smile declaring, “Ordinary is the best of all!”

Child-Like Maturity

Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko is a 2021 anime film directed by Ayumu Watanabe (Children of the Sea, Komi Can’t Communicate), animated by Studio 4C (Children of the Sea, Mind Game), and based on the novel of the same name by Kanako Nishi. Creative producer Sanma Akashiya spearheaded this project in what can be considered a culmination of factors the gods were pushing him towards; whether it be the author lauding his work ethic to that of ukiyo-e artist, Katsushika Hokusai on Mr. Akashiya’s on talk show, Sanma no Manma, to an eventual MRI scan for good measure.

The story proper involves two characters and a question - Nikuko, a vibrant pun-loving mother, and her reserved yet observant daughter, Kikuko; binding them is this central question: how are they related when they both look and act so different? All-in-all a simple, laidback character narrative all set in a small ocean town.

Most of the film is told similarly to J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye - our Holden Caulfield is Kikuko and we come to experience the world through her interactions with the various people of this town, save for a flashback. Kikuko sees her mother as a ball of energy, resiliently bouncing her light to others in the town while also from her past betrayals from greedy boyfriends. Beyond those details Kikuko - along with myself and the audience - are left wondering what Nikuko’s intentions, motivations, and thoughts are. Any sudden shift and decision from her mother may result in both of them moving away for the fifth time. Kikuko’s quiet angst makes for an interesting foil to Nikuko’s energetic spirit - how could Nikuko ever be an adult when she acts so much like a kid and vice versa. This duo specifically examines how different people with complementary dynamics - mother/daughter; expressive/reserved; adult/teenager - embraces change. Nikuko puts a smile and moves on, while Kikuko bottles her worries until the time comes to reluctantly deal with it. Encapsulating this difference is in the school sports festival, Kikuko keeps a straight face in every activity, doing her best to not embarrass herself. Nikuko, on the other hand, makes frequent false starts, wheezes through the track, and gracefully finishes the race…in last place. The day after, Kikuko notes her mom’s notoriety around the town and Nikuko triumphantly declares “They can call me ‘the happy fat lady at the grill.’ They can call you ‘The pretty kid, so unlike her mom.’ But I am Lady Nikuko, and I love it!” If it is not obvious, I love this duo.

Along with this is Kikuko’s own myriad of problems from her rift with her best friend Mary to the mystery of the quiet, yet secretly expressive boy, Ninomiya. These moments further her own self-awareness of her own relational insecurities, quirks, and frustrations. For instance, Kikuko goes with Ninomiya to the Kotobuki Center to see his model. Through an exchange of dopey faces she expresses her anger towards Mary only to realize that Kikuko is the one harboring the most annoyance over anybody in the class. Then another silly-faced exchange only this time, Kikuko wells up, crying knowing she is the immature one.

For all of its charm, it is rather hard to pinpoint where the emphasis may be. Spending time with various characters can leave one wondering where and what the point is. Does it lie in Nikuko’s youthful spirit, Ninomiya’s silly faces, Mary’s yearning for belonging? There are many plot lines and motifs, yet little time for development. As each of the aforementioned interactions, I am left with not knowing much about these side characters as opposed to how each of them shape Kikuko into a more developed person. They operate functionally as opposed to relationally. Of course there are moments of genuine humanity: Ninomiya and Kikuko exchanging weird faces is a cheeky - no pun intended - term of endearment; Nikuko smiling with her pupils visible speaks volumes to the level care she has for those closest to her; Mary running and cursing through the rain is funny. Though I am left with nothing more than just glimpses that define Kikuko as opposed to the people. There seems to be a lot going on beyond the surface that unfortunately gets underdeveloped, thereby dampening the experience and weight of the message. The conflict at hand, more or less, does not get much development until the last leg of the film. Without giving much away, it is a truly impactful theme yet lacks the emotional gut punch due to shaky narrative buildup and execution; it just happens. It feels like a lot has been crammed into 96 minutes.

Perhaps this is myself wanting more connection with the people in this town - Nikuko, Kikuko, the students, the chef, and much more. A more realized world - and maybe a longer run time - would have reinforced the aforementioned motifs that this story explores. I would love to see more of this small town - how in spite of being there for a short amount of time, she is able to find home in herself, family, and community. While Kikuko may have had the most change, it is disappointing to not be able to immerse in its world nor come out of it feeling the journey just as she has. Then again, I cannot deny the small charming moments spread in the movie. They are as ordinary as they are familiar, if not magical. Nikuko, arguably, carries this movie through with a warm beaming smile anyone could ever want. Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko may have its clumsy and undercooked moments - leaving us in its mundane mystery - yet its charm is what stays with you; endearing, weird, and simple just like the mother daughter duo.

Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko is in theaters. Tickets and information here

Many thanks to Sophia Kandah of 42WestLLC and GKids for the screener.

Mamoru Hosoda Interview - Belle

What does social media and Beauty and the Beast have in common? Director and creator, Mamoru Hosoda, has this to say -

We had the opportunity to speak with director and creator, Mamoru Hosoda, about his newest film, Belle. We ask about his:

Inspiration for the movie

Experience in depicting the internet the past twenty years

Thoughts on the power of song

Production during a world-wide pandemic

Many thanks to:

Mamoru Hosoda and Kana Hotta for their time and insight.

GKids and 42 West LLC for the opportunity.

Christian Wiseman for production and video editing.

Dakota McNally for editing the questions.

Misa Villegas, Marvin Hidalgo, and Coyo Poblano for brainstorming questions.

One Piece: Strong World Review

by Jonathan “Joestar” Beltran

One Piece: Strong World is a 2009 movie written by Eiichiro Oda – the creator of One Piece – featuring the ever-charming Straw Hat Pirates on another adventure fighting an overpowered ability: in this case, gravity manipulation. The aforementioned crew decide to go back to their home in the East Blue only to come across a gravity-defying villain, Golden Lion Shiki, in need of a navigator. His efforts lead to the kidnapping of the Straw Hat navigator, Nami, as well scattering the crew on a floating island filled with savage, genetically-mutated monsters. Furthering the dilemma, Shiki presents Nami with an ultimatum – join his crew or see the demise of her friends and home. This is a Nami and Luffy-centric story, focusing on the cost of friendship and one’s personal allegiance in the face of sentimental stakes. This story fits somewhere between the Thriller Bark and Sabaody Archipelago arc (respectively Season 10 and 11).

It is no secret that a lot of One Piece’s notoriety comes from its rather immense episode count. In fact, by the time of this article, it will be celebrating its 1000th episode – a commendable feat for any show. I can say as someone who is on Season 15 – the Fishman Island arc – this journey is an engaging one. The show is fun and filled to the brim with a child-like whimsy that, as a somewhat jaded anime fan, I find incredibly refreshing.

For the first leg of the movie, I was reminded of why I enjoyed the series in the first place. Seeing Luffy witness these ferocious, goofy-looking monsters beating each other up and eventually joining in the fray with his developed powers is nothing short of fun. Even the banter amongst the Straw Hat crew in naively accepting Golden Lion Shiki’s offer to visit the floating island is charming. Not to mention, Shiki is an appropriately intimidating villain – manipulating objects to float, from dumbbells to islands, and even enhancing creatures for an eventual rampage across the world makes him a formidable foe for the Straw Hats.

However, it does come across like any other shonen movie to me: good guys go to a new area, meet bad guy and new characters (which we may never see again in the series), funny antics ensue, first fight ends in failure, then the second fight ends in success thanks to the hero’s ultimate/new ability, and the power of friendship at the very end for a happy ending.

Ultimately a lot of one’s own entertainment involves two factors your initial engagement with the series and, most notably your enjoyment – or more pessimistically, tolerance – for this general shonen movie format. This is not a movie for newcomers; characters are not given much development beyond their unique characteristics and abilities – whether it would be Sanji’s, the Straw Hat’s chef’s, obsession with beautiful women or Zoro’s, the Straw Hat’s ace swordsman’s (and arguably One Piece’s sole “cool” character), three sword technique and tendency to get lost. Crew members are not given much screen time due to the limited runtime and an expansive crew of characters, specifically the mechanic Frankie and historian Nico Robin are sidelined as expository tools for the movie. But other characters received a surprising amount, such as Brook – the skeletal musician. Simply put, if you did your homework, you know what you are getting yourself into. For me, however, even having prior knowledge and familiarity with the series did not make for an enjoyable experience due to the glaring shonen movie format. I already know where the story beats are going to be – Shiki’s nefarious plans are revealed in exposition, Luffy loses the first match, and even Nami’s message – most of it felt predictable.

Even as a film for the fans, I do not think it provides enough fan service as an action shonen. There is not a lot of time dedicated to the Straw Hat crew, and this cannot be more emphasized than the climax when the Straw Hats come in with guns a blazing – shooting Shiki’s men mafioso style. On paper, this is awesome, yet the execution is squandered with little uniqueness: simple explosions, people falling, and still shots. The set piece is budgeted at best and lazy at worst. Put simply, there was a lack of animation or effort put into making these fights flashy and dynamic as they would in the series. Even when they show a moment of the crew fighting with their unique, individual abilities, it is not prominent enough to make for a unique Straw Hat fight.

This movie is not for me. In comparison, I still prefer the zany – albeit budgeted – series over this any day as it provides more time for characters, world-building, and weirdness. If you are a fan of the series, there is charm to be found in small doses. One Piece will always have a massive following – and while this movie does a little of the charm that made the series such a mainstay, it is serviceable at best and does not go above and beyond the general shonen format.

You can watch One Piece: Strong World on select theaters: Sunday November 7 (Dub) and Tuesday November 9 (Sub)

Many thanks to Scott Barretto of Publicity Partners for the screener and review opportunity.

Megumi Tadokoro is a Better Ochako Uraraka

By Dakota McNally

Back in August, I was writing questions for an incredible panel of guests – including the creator of Shokugeki no Soma (Food Wars) – when thought had occurred to me: Megumi and Uraraka from Boku no Hero Academia (My Hero Academia) are a lot alike. Both come from poor families, both want to excel in their profession, and both must struggle against the strongest members of their class. They are also the primary female leads of popular, long-running shonen series and have done a great deal to change the landscape of shonen.

Soon enough, a rather provocative query arose from this comparison: is Megumi Tadokoro a better written Uraraka Ochako?

Before you click away, let me be clear: I love both characters and both series. In early September, I threw up an image of my messy green hair on social media and compared my mop to Deku’s, which has benefitted from some of the best writing in modern anime.

I’m in love with My Hero Academia. And I want to see Uraraka succeed. But the story of Megumi Tadokoro tugs my heart strings in a way I wish Uraraka’s story would continue to do.

And yes, for the sake of an easier read, I will refer to the series by their English names. You can burn me at the stake in the comments.

For anyone less familiar with Food Wars, the series shares much in common with My Hero Academia: Elite, bigger than life academy, star students, and tougher than nails exams and assignments, where merit and hard work define success in their creatively crafted worlds – but always with the looming threat of expulsion for poor performance. Both series believe in the power of hard work and effort, that some are born with privilege, but anybody can find their place in the world if they work hard enough.

I will fully disclaim both series are ongoing, so my opinion on Uraraka’s development might change with future releases. I would love for that to be the case and intend to revisit this piece should my opinion shift.

There will be spoilers for both series. Lots of them. You have been warned.

Who in the world is Uraraka Ochako?

Uraraka launches into the series strong, scoring third in the UA Entrance exam and scoring first in our hearts. Competent, resourceful and optimistic, Uraraka’s poised to become an easy fan favorite. She isn’t infallible, but Uraraka is reliable in a pinch, doing everything in her power to support all who need her. Vouching for Deku’s heroism during the exam, despite him never scoring a point, Uraraka’s the primary reason for Deku’s admittance to UA.

Uraraka uses cunning and creativity to get past the worst the UA Academy can throw at her, while she may not stack up to the likes of Todoroki and Bakugou quite yet, she is a force to be reckoned with. Yet despite these wonderful traits, Uraraka really has few shortcomings: she’s a bit stingy when it comes to spending, but understandably so considering her background. She doesn’t possess an inherently “heroic” reason for becoming a pro, something that would be touched upon thematically by Hero Killer Stain, but this never becomes a direct conflict for her character in the way that it did for Iida. She is laid back, but not to a point of irresponsibility or risking her standing in the class.

To connect with a character means seeing them fail, struggle, and improve, which is why Uraraka’s standout moment in the series comes during her fight against Bakugou at the Sports Festival. There’s a lot at stake for Uraraka here, providing her a chance to gain recognition from future employers as she displays her skills on a nationally televised event. Uraraka remembers her family in this moment, her drive and reason to fight, to give them a better life. This is one of the few moments in the series that we see Uraraka’s motivation given life on screen, fueling her desperation to win in hopes of impressing the agencies watching her match.

She’s also fighting an uphill battle against an opponent with superior reflexes, forced instead to distract and wear down her opponent and fight him indirectly. This moment forces Uraraka to be pushed to her limits, and because she is struggling both emotionally and physically against insurmountable odds, the audience manages to connect with her meaningfully.

When the crowd jeers at Bakugou for going all out against her, and we realize that not only is she is being underestimated because of her power disadvantage, but also, sadly, for being a girl, we feel for her even more. To Uraraka, this unwanted pity is largely embarrassing: she’s attempting to prove her mettle for the top agencies in the country, to secure her future as a professional. When Eraser Head rebukes the crowd, Bakugou’s actions become even more meaningful in the moment: his ferocity comes out of a deep respect for Uraraka’s strength. She is a worthy opponent that he cannot afford to go easy on.

Despite Uraraka’s final gambit, and all of her efforts, Bakugou emerges untouched and she collapses, facing a bitter loss. Bakugou breathes a sigh of relief surviving her attack, however, having recognized just how close she had come to overcoming him. Her fight with Bakugou proves that with training, commitment, and effort, Uraraka can continue to rise in the ranks at UA alongside Deku. This sets up Uraraka’s arc for growth, for further improvement: if she wants to see her dreams come true, to not be underestimated, she has to train and improve herself.

She earns the right to train with Gunhead and develops her martial arts, all as a means to overcome her shortcomings in the sports festival. This shows promise, in the way that Deku’s training to learn Full Cowling gave the audience a measuring stick for his growth towards his goal.

But sadly, Uraraka’s development begins to stagnate past this point. She doesn’t inherently change as a character: her personality, beliefs, and goals never make any significant leaps since the Bakugou fight. Understandably, this can be attributed to a large issue with the show: My Hero Academia large cast provides a lot of ground to cover, and not everybody can receive exceptional development, but unlike Iida and Todoroki, Uraraka’s arc never came to a satisfying conclusion. Todoroki had to accept his father, and the power inherited from him, in order to come to peace with himself and dedicate himself fully to his work. Iida had to come to terms with his brother’s retirement, not allowing revenge to consume him and reinforcing his reasoning for becoming a hero.

Uraraka, in comparison, never really learned anything from her fight with Bakugou. She understands that she needs to improve, but not how to improve as a person. While Uraraka might be getting progressively stronger through training, her growth as a character is never again tied to any major emotional or plot stakes that continue to push her development further. Furthermore, getting stronger does not equate to character development; it’s how a character get stronger, how they change as people, that matters more than the strength itself.

Uraraka does express an admiration, and later attraction, for Deku, and questions if her feelings will get in the way of her work. The problem with the budding relationship between Uraraka and Deku, at this point in the series, is that Uraraka’s romantic feelings change the status quo very little. Had her feelings amounted to a confrontation or friction between her and Deku, this arc could have had potential to explore some interesting themes surrounding her professional goals and private feelings, but this, regrettably, amounted to very little. Even her fight with Toga really had little to do with her feelings for Deku: her desire to protect Deku in that moment didn’t lead her to make any professional blunders, think irrationally or show favoritism. If anything, her development stalls due to this manufactured conflict, seeing as she never takes any risks in revealing her feelings and risking a change in her relationship: nothing has changed.

So, who in the world is Uraraka Ochako?

If every porkchop were perfect, we wouldn’t have Megumi

Enter Megumi Tadokoro. Unlike Uraraka, she starts at the bottom of her class and with plenty of flaws. Her stage fright and inability to handle pressure makes her underperform, barely making it into the high school division of Totsuki Culinary Academy. While kind, nurturing, and determined, Totsuki Academy is unforgiving to those unable to stand on her own. She lived in the shed of Polar Star Dormitory until she could pass the entrance exam, and even after passing, she finds herself relying on Soma’s creative thinking and talent to avoid expulsion. Megumi has a lot of growing to do.

Megumi’s faces her first major challenge and chance for growth in her battle against a Totsuki Academy alumnus Kojiro, who, much like Bakugou, is clearly at a different level than Megumi at this point in the series. Despite being outmatched in the end, Megumi’s talent managed to move her opponent, Kojiro, who votes for her dish, which causes the duel to end in a tie. This moment becomes the first instance of anyone recognizing her talent as a chef and her first step towards independence.

Megumi not only holds her own in the buffet challenge the next day but manages to succeed using hospitality dining—experience gained from her family’s inn. This reminds us of her background and her motivation to keep her family out of poverty; Megumi draws from her past experiences to make her a more capable person in the present. Megumi’s outstanding efforts earn her a candidacy to compete in the 43rd Annual Totsuki Autumn Election with the best chefs in her class. Not only is Megumi able to stand on her own, but she can compete among the best, furthering her confidence.

Megumi’s character arc consistently oozes character development, while weaving a fantastic story of an underdog motivated to do good for her family, and finding her roots helps her to rise to the top. Her candidacy is met by a jeering audience, stoutly against her participation. To the student body, Megumi is still considered one of the worst performing students on campus, refuses to believe in her professional turnabout. Her reputation, and everything that she had fought for up to this point, is at stake: if she fails here or refuses to participate, she risks losing faith in herself, and her development up until this point can very easily be undone. Despite the odds, Megumi overcomes stage fright on the most hostile stage imaginable and succeeds in the preliminaries, gaining entrance into the main tournament.

Megumi surpasses herself, making it all the way to the quarterfinals. Her loss to Ryo becomes all the more bitter because she strives for victory. Compared to the girl who fear expulsion mere months ago, Megumi has changed significantly: she hates losing because she now believes that she can win. More importantly, she also learns that relying on others will only get her so far: she will have to rise to the top on her own. The audience commends her participation on how far she’s managed to come, and she gains not just respect among her peers, but a newfound respect for herself.

Megumi continues to grow by leaps and bound after the Autumn Election, even advising Soma, the main character, in future arcs. Her work study sees her improving the restaurant that she was assigned to, even impressing Erina, the Gordon Ramsay of the series. She defends Polar Star Dormitory from its closure, putting her career on the line to defend the dormitory that had encouraged her growth. She’s no longer relying on others but actively helping and fighting for them. Her growth is not only prominent, but measurable in both her skill as a chef and in her character. Her bitter work and lifechanging journey will eventually earn her the 10th seat of the Elite Ten by her second year at Totsuki Academy, and she is unrecognizable from her season one self. Megumi, even among the large cast of Food Wars, is always at the forefront of the series. We see her fail, struggle, and overcome obstacles on screen along with the titular hero, and grow as a person because of her experiences.

So what?

Uraraka and Megumi may have come from similar backgrounds and have similar goals, but they are still different characters. Uraraka does not struggle with confidence and she is more independent and capable. Megumi’s arc, meanwhile, is focused on her gaining competence and independence from others and standing on her own.

The biggest difference between these characters is that Megumi changes throughout the story significantly, where Uraraka remains the same.

Megumi is arguably much more like Deku upon second glance, somebody who started with nothing who was given a chance by someone to blossom and became something on their own. Deku’s development works so well because there are stakes tied to his need to get stronger. All Might, the Symbol of Peace, is gradually running out of time as his health worsens and passed down his power to Deku. Deku has to grasp not just strength, but responsibility and a purpose for wanting to be All Might’s successor as he gradually develops. As a result, Deku is forced to grow – from someone who idealistically aspires to be a hero to becoming the successor for the Symbol of Peace. His development shapes Deku from a quirk-less kid with a dream into a responsible young man with plenty of chips on his shoulder.

Deku has to grow up, and so does Megumi: like Deku, she had to aspire to be more, not just to support her family but to improve herself in order to succeed.

The mutual theme of Food Wars and My Hero Academia is the notion that hard work and dedication leads to success in life. Megumi started out undervaluing herself, all because she cracked under pressure and failed to believe in her own strengths. Watching Megumi progress and grow, much like Deku, allowed us to connect with her and cheer her on, making her one of the strongest, most developed characters in the series next to Soma, the main character, and Erina, an antagonist turned anti-hero.

Uraraka deserves the same level of development, but without any real flaws, her character will continue to lack growth. Given an arc to expose her character flaws more prominently and given the chance and the stakes to improve herself, Uraraka can become more than what she seems. Who is Uraraka Ochako, what makes her tick, and most of all, how does she need to change? For now, her fight with Bakugou continues to be one of the most memorable moments in the series, and with some newfound momentum and attention, perhaps Uraraka will capture the hearts of fans once more.

Go beyond, Uraraka! Plus Ultra!